* Pay in 3 equal payments – first when your order is confirmed, second 30 days later and third 60 days later. No interest, no fees.

Please note: Pay In 3 is only applicable to orders with a value of £1500 or less.

Choose Klarna in checkout to apply for a finance option. 10% deposit required as standard (excluding Pay In Three).

Borrowing more than you can afford or paying late may negatively impact your financial status and ability to obtain credit.

REPRESENTATIVE EXAMPLE

Cash/purchase price: £1200. Deposit: £120. Total amount of credit: £1080.

Rate of interest: 9.9% p.a. (fixed). Duration of the agreement: 24 months.

Monthly repayments: £49.58. Interest: £109.91. Total amount payable: £1309.91.

The Representative APR: 9.9% APR Representative.

Tiger Sheds is a trading name of Woodlands Home And Garden Group Limited (reg. address: Calverley Lane, Leeds, LS13 1NP)

which is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA FRN 914564) and acts as a credit intermediary

and not a lender, offering credit products provided exclusively by Klarna Financial Services UK Limited. Please note

that Pay in 3 instalments agreements are not regulated by the FCA. Finance is only available to permanent UK residents

aged 18+, subject to status, T&Cs and late fees apply.

Klarna.com/uk/terms-and-conditions

Tiger Spotlight | Victoria Justice, DIY & Home Interiors Blogger

Tiger Spotlight | Victoria Justice, DIY & Home Interiors Blogger

How to Fit Guttering on a Shed

How to Fit Guttering on a Shed

How to Store Garden Tools

How to Store Garden Tools

How to Keep your Shed Cool

How to Keep your Shed Cool

Ultimate Shed Accessories Guide

Ultimate Shed Accessories Guide

The Story Behind Merseyside Sheds

The Story Behind Merseyside Sheds

How to Build a Garden Workshop

How to Build a Garden Workshop

Tiger Spotlight | Hayley Stuart, DIY & Interiors Blogger

Tiger Spotlight | Hayley Stuart, DIY & Interiors Blogger

Top Garden Trends for 2024

Top Garden Trends for 2024

Meet the Tiger Team | Dave Hansell, Warehouse Senior Operative

Meet the Tiger Team | Dave Hansell, Warehouse Senior Operative

Ideas to Create the Ultimate Garden Workout Space

Ideas to Create the Ultimate Garden Workout Space

Meet the Tiger Team | Adam Deary, Showsite Manager

Meet the Tiger Team | Adam Deary, Showsite Manager

Meet the Tiger Team | Paul Dixon, Driver

Meet the Tiger Team | Paul Dixon, Driver

How to Felt a Shed Roof

How to Felt a Shed Roof

Meet the Tiger Team | Eric, Brand Ambassador

Meet the Tiger Team | Eric, Brand Ambassador

Meet the Tiger Team | Stephen Hogg, Product Designer

Meet the Tiger Team | Stephen Hogg, Product Designer

Meet the Tiger Team | Agata Choma, Head of Operations

Meet the Tiger Team | Agata Choma, Head of Operations

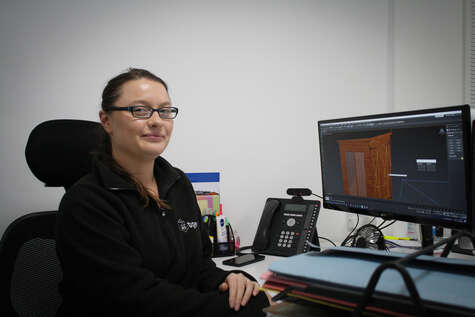

Meet the Tiger Team | Katrina Johnson, Lead Designer

Meet the Tiger Team | Katrina Johnson, Lead Designer

A Great Idea Was Hatched from a Tiger

A Great Idea Was Hatched from a Tiger

Five Garden Updates that can Devalue a Home

Five Garden Updates that can Devalue a Home